Building SAGA optimization for Dask arrays

This work is supported by ETH Zurich, Anaconda Inc, and the Berkeley Institute for Data Science

At a recent Scikit-learn/Scikit-image/Dask sprint at BIDS, Fabian Pedregosa (a machine learning researcher and Scikit-learn developer) and Matthew Rocklin (Dask core developer) sat down together to develop an implementation of the incremental optimization algorithm SAGA on parallel Dask datasets. The result is a sequential algorithm that can be run on any dask array, and so allows the data to be stored on disk or even distributed among different machines.

It was interesting both to see how the algorithm performed and also to see the ease and challenges to run a research algorithm on a Dask distributed dataset.

Start

We started with an initial implementation that Fabian had written for Numpy arrays using Numba. The following code solves an optimization problem of the form

\[min_x \sum_{i=1}^n f(a_i^t x, b_i)\]import numpy as np

from numba import njit

from sklearn.linear_model.sag import get_auto_step_size

from sklearn.utils.extmath import row_norms

@njit

def deriv_logistic(p, y):

# derivative of logistic loss

# same as in lightning (with minus sign)

p *= y

if p > 0:

phi = 1. / (1 + np.exp(-p))

else:

exp_t = np.exp(p)

phi = exp_t / (1. + exp_t)

return (phi - 1) * y

@njit

def SAGA(A, b, step_size, max_iter=100):

"""

SAGA algorithm

A : n_samples x n_features numpy array

b : n_samples numpy array with values -1 or 1

"""

n_samples, n_features = A.shape

memory_gradient = np.zeros(n_samples)

gradient_average = np.zeros(n_features)

x = np.zeros(n_features) # vector of coefficients

step_size = 0.3 * get_auto_step_size(row_norms(A, squared=True).max(), 0, 'log', False)

for _ in range(max_iter):

# sample randomly

idx = np.arange(memory_gradient.size)

np.random.shuffle(idx)

# .. inner iteration ..

for i in idx:

grad_i = deriv_logistic(np.dot(x, A[i]), b[i])

# .. update coefficients ..

delta = (grad_i - memory_gradient[i]) * A[i]

x -= step_size * (delta + gradient_average)

# .. update memory terms ..

gradient_average += (grad_i - memory_gradient[i]) * A[i] / n_samples

memory_gradient[i] = grad_i

# monitor convergence

print('gradient norm:', np.linalg.norm(gradient_average))

return x

This implementation is a simplified version of the SAGA

implementation

that Fabian uses regularly as part of his research, and that assumes that $f$ is the logistic loss, i.e., $f(z) = \log(1 + \exp(-z))$. It can be used to solve problems with other values of $f$ by overwriting the function deriv_logistic.

We wanted to apply it across a parallel Dask array by applying it to each chunk of the Dask array, a smaller Numpy array, one at a time, carrying along a set of parameters along the way.

Development Process

In order to better understand the challenges of writing Dask algorithms, Fabian did most of the actual coding to start. Fabian is good example of a researcher who knows how to program well and how to design ML algorithms, but has no direct exposure to the Dask library. This was an educational opportunity both for Fabian and for Matt. Fabian learned how to use Dask, and Matt learned how to introduce Dask to researchers like Fabian.

Step 1: Build a sequential algorithm with pure functions

To start we actually didn’t use Dask at all, instead, Fabian modified his implementation in a few ways:

- It should operate over a list of Numpy arrays. A list of Numpy arrays is similar to a Dask array, but simpler.

- It should separate blocks of logic into separate functions, these will

eventually become tasks, so they should be sizable chunks of work. In this

case, this led to the creating of the function

_chunk_sagathat performs an iteration of the SAGA algorithm on a subset of the data. - These functions should not modify their inputs, nor should they depend on global state. All information that those functions require (like the parameters that we’re learning in our algorithm) should be explicitly provided as inputs.

These requested modifications affect performance a bit, we end up making more copies of the parameters and more copies of intermediate state. In terms of programming difficulty this took a bit of time (around a couple hours) but is a straightforward task that Fabian didn’t seem to find challenging or foreign.

These changes resulted in the following code:

from numba import njit

from sklearn.utils.extmath import row_norms

from sklearn.linear_model.sag import get_auto_step_size

@njit

def _chunk_saga(A, b, n_samples, f_deriv, x, memory_gradient, gradient_average, step_size):

# Make explicit copies of inputs

x = x.copy()

gradient_average = gradient_average.copy()

memory_gradient = memory_gradient.copy()

# Sample randomly

idx = np.arange(memory_gradient.size)

np.random.shuffle(idx)

# .. inner iteration ..

for i in idx:

grad_i = f_deriv(np.dot(x, A[i]), b[i])

# .. update coefficients ..

delta = (grad_i - memory_gradient[i]) * A[i]

x -= step_size * (delta + gradient_average)

# .. update memory terms ..

gradient_average += (grad_i - memory_gradient[i]) * A[i] / n_samples

memory_gradient[i] = grad_i

return x, memory_gradient, gradient_average

def full_saga(data, max_iter=100, callback=None):

"""

data: list of (A, b), where A is a n_samples x n_features

numpy array and b is a n_samples numpy array

"""

n_samples = 0

for A, b in data:

n_samples += A.shape[0]

n_features = data[0][0].shape[1]

memory_gradients = [np.zeros(A.shape[0]) for (A, b) in data]

gradient_average = np.zeros(n_features)

x = np.zeros(n_features)

steps = [get_auto_step_size(row_norms(A, squared=True).max(), 0, 'log', False) for (A, b) in data]

step_size = 0.3 * np.min(steps)

for _ in range(max_iter):

for i, (A, b) in enumerate(data):

x, memory_gradients[i], gradient_average = _chunk_saga(

A, b, n_samples, deriv_logistic, x, memory_gradients[i],

gradient_average, step_size)

if callback is not None:

print(callback(x, data))

return x

Step 2: Apply dask.delayed

Once functions neither modified their inputs nor relied on global state we went

over a dask.delayed example,

and then applied the @dask.delayed decorator to the functions that

Fabian had written. Fabian did this at first in about five minutes and to our

mutual surprise, things actually worked

@dask.delayed(nout=3) # <<<---- New

@njit

def _chunk_saga(A, b, n_samples, f_deriv, x, memory_gradient, gradient_average, step_size):

...

def full_saga(data, max_iter=100, callback=None):

n_samples = 0

for A, b in data:

n_samples += A.shape[0]

data = dask.persist(*data) # <<<---- New

...

for _ in range(max_iter):

for i, (A, b) in enumerate(data):

x, memory_gradients[i], gradient_average = _chunk_saga(

A, b, n_samples, deriv_logistic, x, memory_gradients[i],

gradient_average, step_size)

cb = dask.delayed(callback)(x, data) # <<<---- Changed

x, cb = dask.persist(x, cb) # <<<---- New

print(cb.compute()

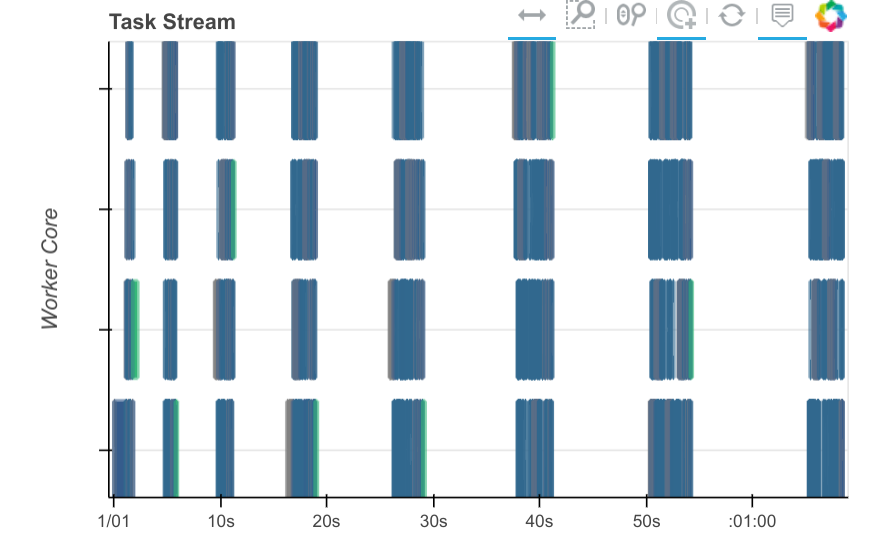

However, they didn’t work that well. When we took a look at the dask dashboard we find that there is a lot of dead space, a sign that we’re still doing a lot of computation on the client side.

Step 3: Diagnose and add more dask.delayed calls

While things worked, they were also fairly slow. If you notice the dashboard plot above you’ll see that there is plenty of white in between colored rectangles. This shows that there are long periods where none of the workers is doing any work.

This is a common sign that we’re mixing work between the workers (which shows up on the dashbaord) and the client. The solution to this is usually more targetted use of dask.delayed. Dask delayed is trivial to start using, but does require some experience to use well. It’s important to keep track of which operations and variables are delayed and which aren’t. There is some cost to mixing between them.

At this point Matt stepped in and added delayed in a few more places and the dashboard plot started looking cleaner.

@dask.delayed(nout=3) # <<<---- New

@njit

def _chunk_saga(A, b, n_samples, f_deriv, x, memory_gradient, gradient_average, step_size):

...

def full_saga(data, max_iter=100, callback=None):

n_samples = 0

for A, b in data:

n_samples += A.shape[0]

n_features = data[0][0].shape[1]

data = dask.persist(*data) # <<<---- New

memory_gradients = [dask.delayed(np.zeros)(A.shape[0])

for (A, b) in data] # <<<---- Changed

gradient_average = dask.delayed(np.zeros)(n_features) # Changed

x = dask.delayed(np.zeros)(n_features) # <<<---- Changed

steps = [dask.delayed(get_auto_step_size)(

dask.delayed(row_norms)(A, squared=True).max(),

0, 'log', False)

for (A, b) in data] # <<<---- Changed

step_size = 0.3 * dask.delayed(np.min)(steps) # <<<---- Changed

for _ in range(max_iter):

for i, (A, b) in enumerate(data):

x, memory_gradients[i], gradient_average = _chunk_saga(

A, b, n_samples, deriv_logistic, x, memory_gradients[i],

gradient_average, step_size)

cb = dask.delayed(callback)(x, data) # <<<---- Changed

x, memory_gradients, gradient_average, step_size, cb = \

dask.persist(x, memory_gradients, gradient_average, step_size, cb) # New

print(cb.compute()) # <<<---- changed

return x

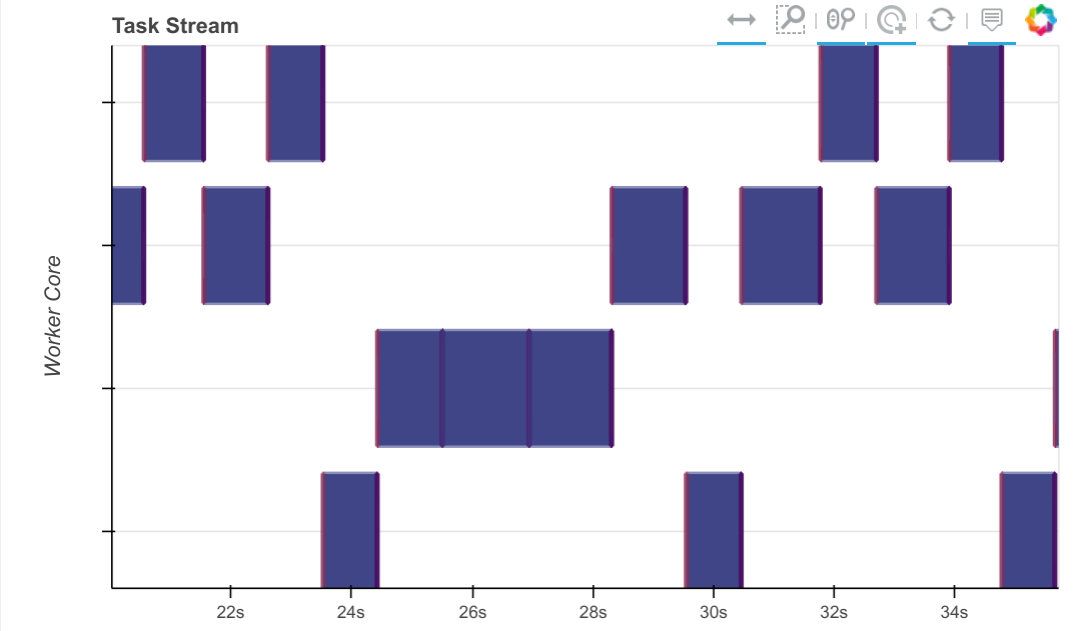

From a dask perspective this now looks good. We see that one partial_fit

call is active at any given time with no large horizontal gaps between

partial_fit calls. We’re not getting any parallelism (this is just a

sequential algorithm) but we don’t have much dead space. The model seems to

jump between the various workers, processing on a chunk of data before moving

on to new data.

Step 4: Profile

The dashboard image above gives confidence that our algorithm is operating as it should. The block-sequential nature of the algorithm comes out cleanly, and the gaps between tasks are very short.

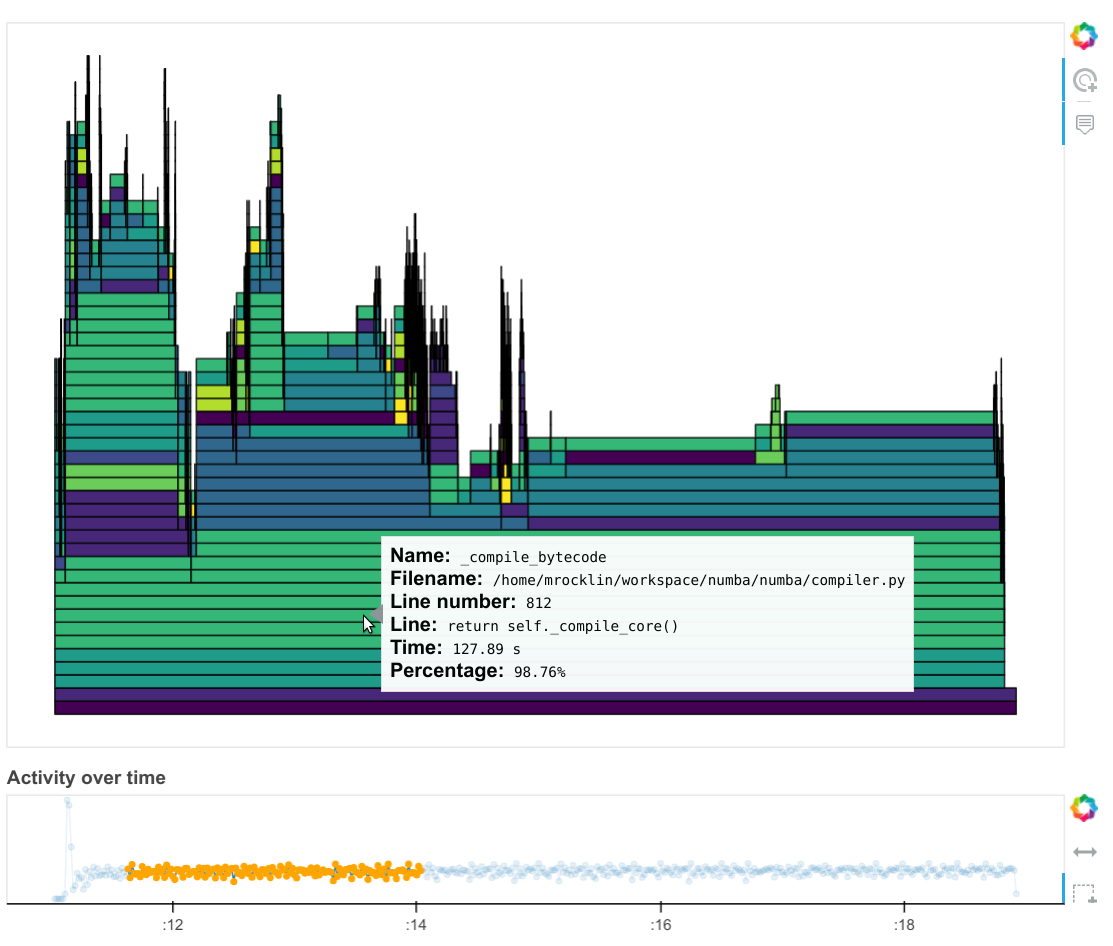

However, when we look at the profile plot of the computation across all of our cores (Dask constantly runs a profiler on all threads on all workers to get this information) we see that most of our time is spent compiling Numba code.

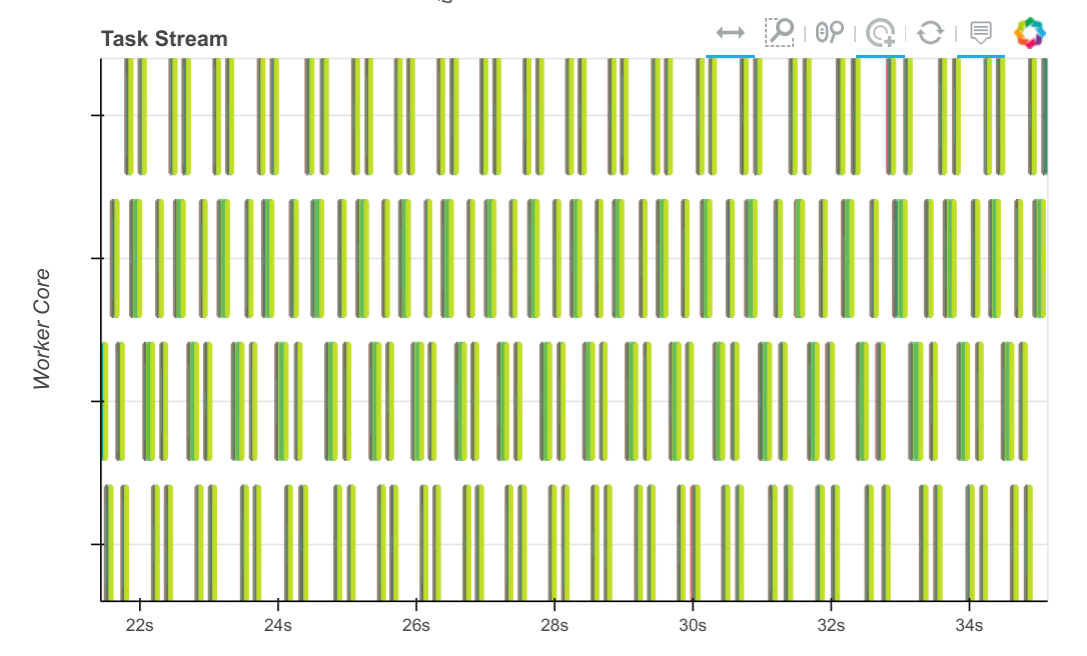

We started a conversation for this on the numba issue tracker which has since been resolved. That same computation over the same time now looks like this:

The tasks, which used to take seconds, now take tens of milliseconds, so we can process through many more chunks in the same amount of time.

Future Work

This was a useful experience to build an interesting algorithm. Most of the work above took place in an afternoon. We came away from this activity with a few tasks of our own:

- Build a normal Scikit-Learn style estimator class for this algorithm so that people can use it without thinking too much about delayed objects, and can instead just use dask arrays or dataframes

- Integrate some of Fabian’s research on this algorithm that improves performance with sparse data and in multi-threaded environments.

- Think about how to improve the learning experience so that dask.delayed can teach new users how to use it correctly

Links

- Notebooks for different stages of SAGA+Dask implementation

- Scikit-Learn/Image + Dask Sprint issue tracker

- Paper on SAGA algorithm

- Fabian’s more fully featured non-Dask SAGA implementation

- Numba issue on repeated deserialization

blog comments powered by Disqus